- HELOC Rates Retreat Again, Hitting Year-End Lows

- Loan delinquencies trending down in senior living, rising in skilled nursing

- CFPB Alleges Berkshire Hathaway Subsidiary Originated Unaffordable Housing Loans

- Here’s how to decide on the right student loan repayment plan for you

- CFPB says unit of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway ignored red flags in manufactured home loans

Seth Dunbar and Kelly Klemme

Bạn đang xem: Eleventh District community banks outperform peers despite weaker credit quality

Eleventh District community banks—institutions with less than $10 billion in assets—outperformed U.S. community banks overall through third quarter 2024. Such institutions account for 96 percent of banks and 39 percent of assets in Texas, northern Louisiana and southern New Mexico. Eleventh District banks’ return on average assets outdid the nation, even as troubled commercial real estate loans drove an increase in the noncurrent loan rate.

Eleventh District community banks outpaced their peers nationally in profitability and loan grown during the first three quarters of 2024. However, loan growth slowed for both groups.

Credit quality remains relatively benign despite modest weakening due to troubled commercial real estate loans. That weakening has prompted concern about lower loan loss reserves among community banks with concentrations of commercial real estate loans.

These reserve-level considerations, especially among smaller institutions, may be connected to the adoption of the current expected credit losses methodology, also known as CECL, in January 2023. Generally speaking, CECL requires a broad assessment of current and future economic conditions when considering provisioning for possible future loan losses.

At the same time, community banks have been able to offset unrealized losses on their debt securities holdings with higher retained earnings, increasing their capital cushion.

There are 426 banks with assets under $10 billion in the Eleventh District, which comprises Texas, southern New Mexico and northern Louisiana. These community banks account for 97 percent of banks headquartered in the Eleventh District and 39 percent of assets.

Across the U.S., community banks account for 97 percent of banks and 15 percent of assets.

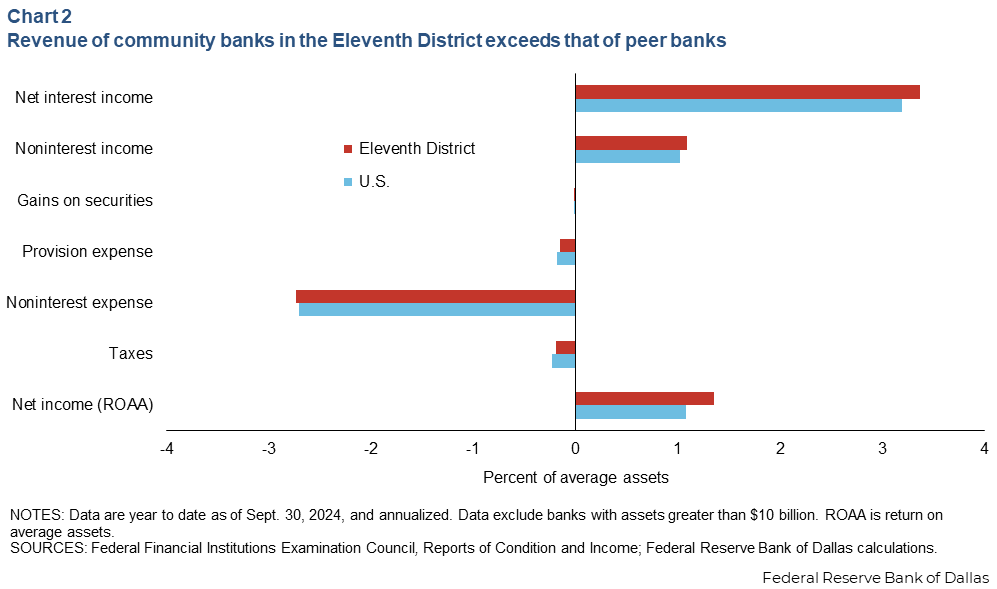

Eleventh District community bank revenue boosts profitability

Community banks in the Eleventh District have been consistently more profitable than their peers nationally (Chart 1 ). Through the first three quarters of 2024, area community banks earned a return on average assets of 1.35 percent compared with 1.08 percent for their U.S. peers.

The above-peer performance can be attributed to higher revenue, both net interest income and noninterest income (Chart 2).

District community banks’ net interest margin was 3.60 percent, 20 basis points (0.20 percentage points) higher than their peers nationally, during the first nine months of the year. The area banks’ noninterest income as a percent of average assets was 1.09 percent, 19 basis points higher than their counterparts across the country.

Meanwhile, district community banks’ provision expense, the amount set aside for loans unlikely to be repaid, and noninterest expense were roughly in line with peer banks.

Net interest margins for community banks declined slightly through the third quarter of 2024. Banks faced greater competition for typically inexpensive deposits amid rising rates and higher interest expense that outpaced increases in interest income.

Xem thêm : Why are mortgage rates still rising? – Deseret News

District community banks maintained net interest margins that exceeded their peers nationally by continuing to fund a larger share of assets (in banking parlance, assets are generally loans) with noninterest-bearing deposits (often deposits in checking accounts). At the same time, a smaller share of assets was backed by higher-cost funding, such as certificates of deposit (CDs) and Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) advances.

Noninterest-bearing deposits amounted to 24 percent of assets at Eleventh District community banks, compared with 19 percent of assets at community banks nationally. CDs and FHLB advances equaled 24 percent of assets at district community banks versus 27 percent of assets for community banks nationally.

Recent net-interest margin compression may continue if the competition for deposits—often requiring banks to pay higher rates of interest on deposits—prevents these institutions from realizing gains attributable to recent Federal Reserve decreases to the federal funds policy rate.

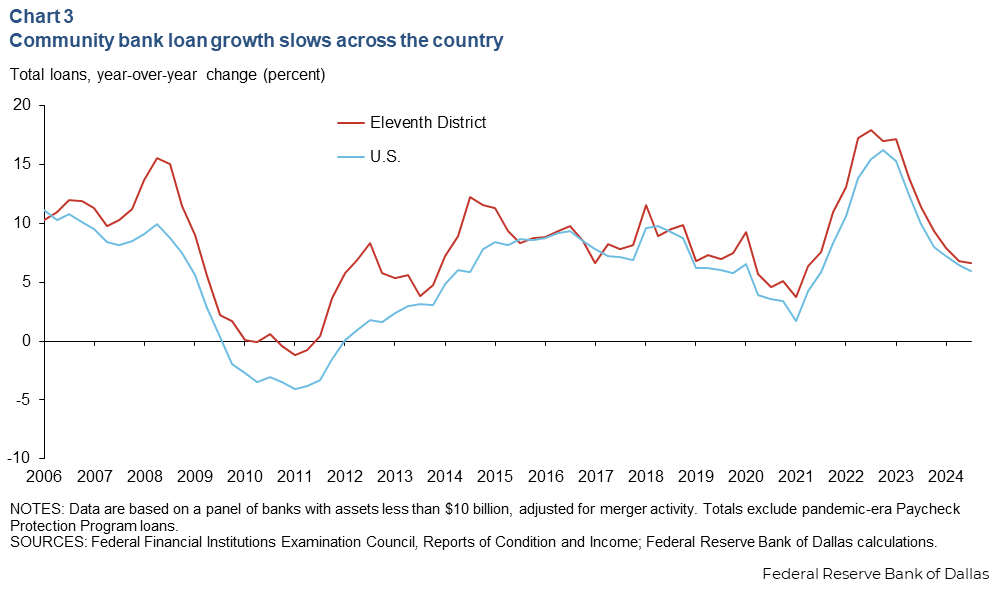

Loan growth slows as rates rise, demand wanes

Until recently, loan growth for Eleventh District community banks surpassed that of their peers across the county. But growth for both groups slowed toward long-term normalized rates as interest rates rose and damped demand (Chart 3).

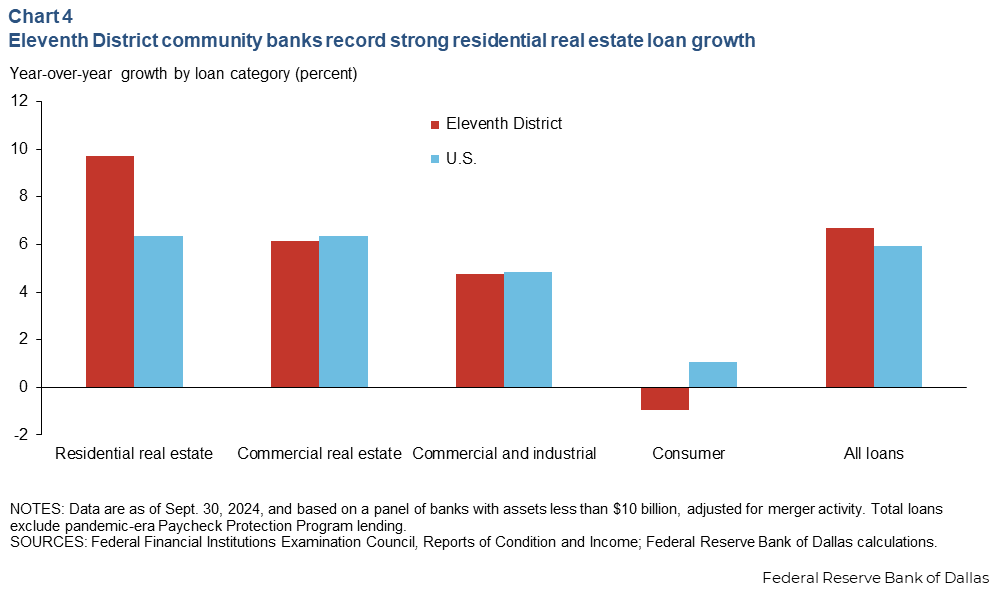

While there has been a slowdown in community bank loan growth across loan types, residential real estate loan growth in the Eleventh District exceeded that of community banks nationally year over year at the end of September (Chart 4).

Based on anecdotal information, in-migration to Texas may be driving some of this residential real estate lending growth. District community banks also reported a decline in consumer loans from a year ago, in line with responses to the Dallas Fed’s October Banking Conditions Survey, which pointed to a drop in consumer loan volume.

Overall credit quality remains benign despite modest weakening

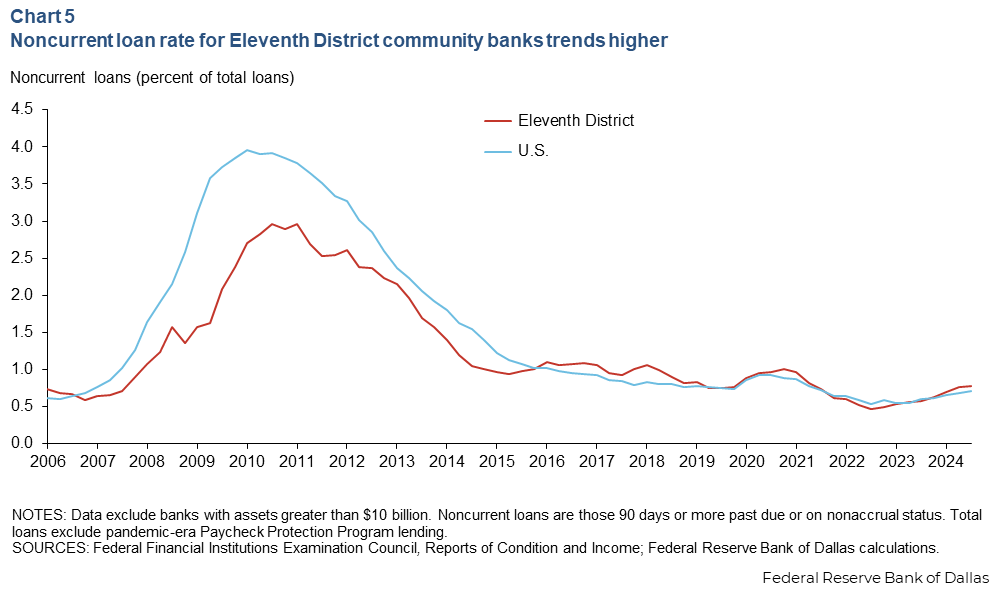

Asset quality measures for community banks remain relatively benign , although there has been an uptick in the share of Eleventh District loans that are noncurrent—past due 90 days or more or on nonaccrual status (no longer generating interest income)—in recent quarters (Chart 5 ).

The noncurrent loan rate for Eleventh District community banks has been increasing since mid-2022 and was 0.78 percent as of Sept. 30, 2024. While the rate is low relative to levels seen in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis (2008), the trend is notable, especially because troubled commercial real estate loans have driven the increase. Total noncurrent loans at Eleventh District community banks are up $790 million since mid-2022, with commercial real estate loans accounting for more than two-thirds of the overall increase.

This rise is concerning, as the office building sector struggles with soft postpandemic occupancy, the multifamily sector deals with excess supply in many markets and refinancing remains difficult given relatively elevated interest rates.

The Eleventh District has a slightly larger share of commercial real estate-concentrated community banks than the U.S. overall, 32 percent versus 29 percent as of Sept. 30.

In this context, commercial real estate concentration is defined as construction loans equal to 100 percent or more of Tier 1 capital (primarily a bank’s equity capital) plus loan loss reserves or nonowner-occupied commercial real estate loans equal to 300 percent or more of Tier 1 capital plus reserves. Nonowner-occupied commercial real estate loans are defined as construction loans, loans secured by multifamily or nonowner-occupied nonfarm nonresidential property, and loans for commercial real estate acquisition and development.

Xem thêm : New PSLF Buyback Program Could Help Some Borrowers Get Student Forgiveness Sooner

Banks, particularly those with commercial real estate concentrations, must maintain adequate loan loss reserves should market conditions deteriorate further. Despite the uncertainty and heightened risk within the commercial real estate sector, aggregate results show that community banks with commercial real estate concentrations tend to have lower loan loss reserves to cover such potential losses.

The allowance for credit losses was 1.20 percent of total loans at Eleventh District community banks with concentrations of commercial real estate as of Sept. 30, 6 basis points lower than for their district counterparts without such a concentration.

Comparable figures for U.S. community banks show even more disparity, with a reserve ratio of 1.16 percent for commercial real estate-concentrated U.S. community banks, compared with 1.34 percent for nonconcentrated community institutions nationally.

Eleventh District banking contacts have shared that they believe the adoption of the CECL methodology for recognizing credit losses has led to lower rates of provisioning in some cases relative to previous methods.

Research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City suggests that one possible explanation is that CECL did not universally increase provisioning across community banks. In fact, just 35 percent of community banks reported an increase in allowance for credit losses at CECL adoption. This is likely due to greater reliance on qualitative factors before CECL was implemented.

Community banks boost capital ratios

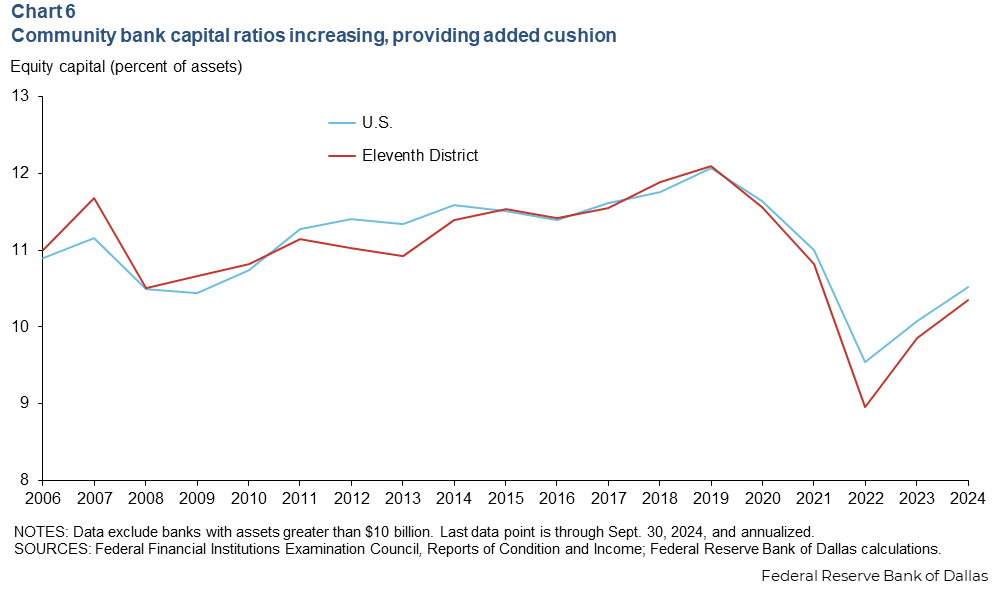

While loan loss reserves are the first line of defense against deteriorating credit quality, banks also hold capital as an additional cushion to absorb losses, and community bank equity capital ratios have been trending up since 2022 (Chart 6).

As interest rates rose beginning in March 2022, the value of community bank securities holdings declined. The price of debt issues, such as Treasuries, moves inversely to interest rates. Thus, the rising rates created a drag on equity capital in the form of unrealized losses. Community banks have offset these losses by increasing retained earnings, boosting overall equity capital ratios.

Area community banks likely to keep outperforming peers

Eleventh District community banks will likely continue to outperform their nationwide peers in terms of profitability, given their larger share of noninterest-bearing deposits.

A steepening yield curve in 2025, in which rates on longer-term Treasuries are greater than those for shorter-term maturities, should also boost bank profits. It allows area community banks to borrow money at lower rates and lend at higher rates, bolstering net interest margin.

Risks to this outlook include deteriorating credit quality, which would require higher provision expense to offset loan losses, and increased net interest margin compression due to deposit competition.

About the authors

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Nguồn: https://marketeconomy.monster

Danh mục: News